When I was asked to speak upon this part of the topic I found my ideas hard to formulate. There is no doubt there are two sides to the question of how much social work a community can afford, and that we can look at it from two different angles. The community has made up its mind to take over the task of social reconstruction, which means all of those old forms of charity which we now describe by the new phrases. We learned long ago to take care of the sick and of the aged, -- all of those old forms of charity which we now describe by the new phrases. We learned long ago to take care of the sick and of the aged, -- all of those forms of charity which are now passing into the realm of taxable community activities. There is no doubt we are being challenged, as we ought to be. I think it is possible there are much too many kinds of social service, and too many forms of any one kind, and I think we would all be happy to have a Taylor System applied to our work, so that we might get rid of wasted time and effort. Therefore, it seems to me that the community chest expresses and perhaps vocalizes an attempt on the part of many givers to get a clear idea of what we are doing and how far it is worth doing; we welcome that challenge, and so far as it is being applied in that spirit we are glad to have it done. There is one aspect of it which we recognize, -- the danger of looking at social work so exclusively from the business point of view that we will apply to it tests which are wholly irrelevant and impossible to apply to parts of the thing which social work is trying to do. It is here the challenge comes in regard to how much [page 2] the community can afford from the ethical standpoint. We have a pretty large business side in social work. An old friend of mine who is responsible for the welfare of nineteen hundred thousand people and has on her staff [268] workers, has found that among these people living in five different communities she knows the exact nutrition status of every child. She knows other things which most of us do not know about our workers, our neighbors. On the business side social workers measure up fairly well.

Are we doing our duty on the ethical side? Are we giving the community a chance to judge day by day how we are doing from the ethical standpoint? Here I believe we are perhaps falling down. Social workers are required to meet situations which should not occur if the ethical standards of the community were higher and here social workers have a right to push their conclusions. It took, for instance, a long time for Beatrice Webb to understanding the ethical aspects connected with the sweating system. We have been stirred by reading recently what one woman did in a curiously conscientious effort to understand what was about her. She had an intolerable curiosity about the lives of the poor. She made an analysis of the sweating system and reported that any man who bought a suit that was made under the sweating system allowed himself to be pauperized, -- pauperized by the husband of the woman who only partly supported her, so that she must work part of the time, just as much as he would have been if he had stood on the street corner and asked for half his wages. She brought home to the consciousness of many people that a consumer could be pauperized and so be to blame for shocking industrial conditions quite as much as the employer of sweated labor, and as the rightminded people in the community who objected to subsidized wages, and that if enough people had arrived at that sense of unwillingness [page 3] to be pauperized the whole question of sweated labor would have been taken care of from the ethical standpoint. Few social workers are able to do what Beatrice Webb did because they do not give to the subjects that confront them that personal, intellectual effort. That ↑Take↓ that matter that was brought to our attention in the last issue of The Survey, a study of the number of young people between the ages of sixteen and eighteen who meet with accidents in industry because they are bungling, and do not give attention to their monotonous work, and so are hurt. It is an attempt on the part of Nature herself to protect them. In the minority report on the English Poor Law, made twelve or fifteen years ago, England was told, and through that report all the English speaking world learned, that it was better ↑not↓ to put young people between sixteen and eighteen at work which did not have some educational content, and that England was preparing for herself a new crop of dependents and unemployables because she was not educating her working young men and women during those years when they might be most easily educated and when they revolted most desperately against the type of work they had to do. If we had applied that suggestion in our cities of course those terrible accidents would have been avoided because of the ethical sense on the part of the community as a whole which might or might not have expressed itself in legislation and protected those young people. We want them to work, we want them to learn to work, and to bring wages home to their families, but certainly a community should have enough ingenuity and enough work to be done to provide its young people with work that has some educational value and not tire them out before the long life of labor that is before them has fairly begun.

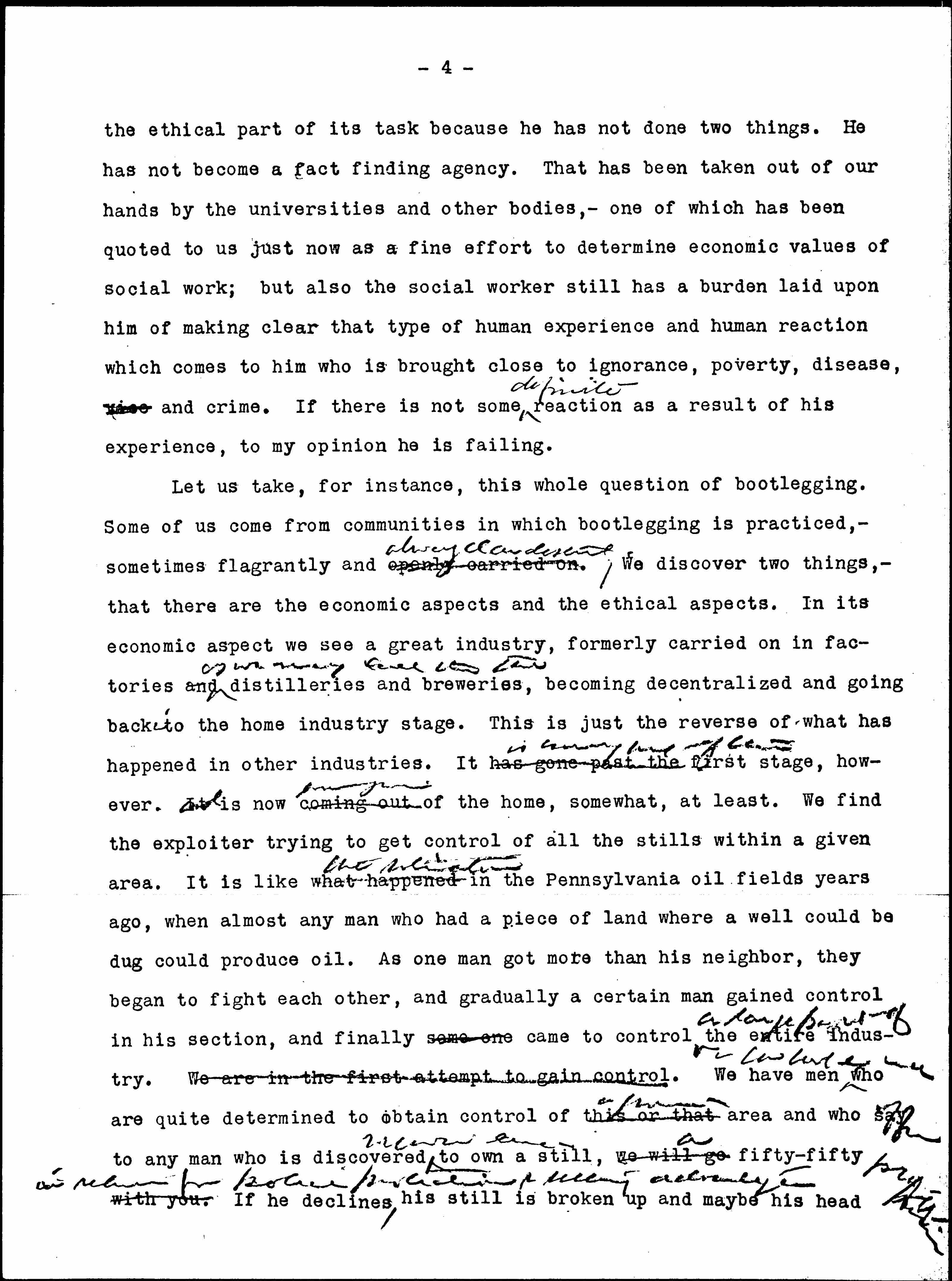

One could go on and challenge social work for not making clear [page 4] the ethical part of its task because he has not done two things. He has not become a fact finding agency. That has been taken out of our hands by the universities and other bodies, -- one of which has been quoted to us just now as a fine effort to determine economic values of social work; but also the social worker still has a burden laid upon him of making clear that type of human experience and human reaction which comes to him who is brought close to ignorance, poverty, disease, vice and crime. If there is not some ↑definite↓ reaction as a result of his experience, to my opinion he is failing.

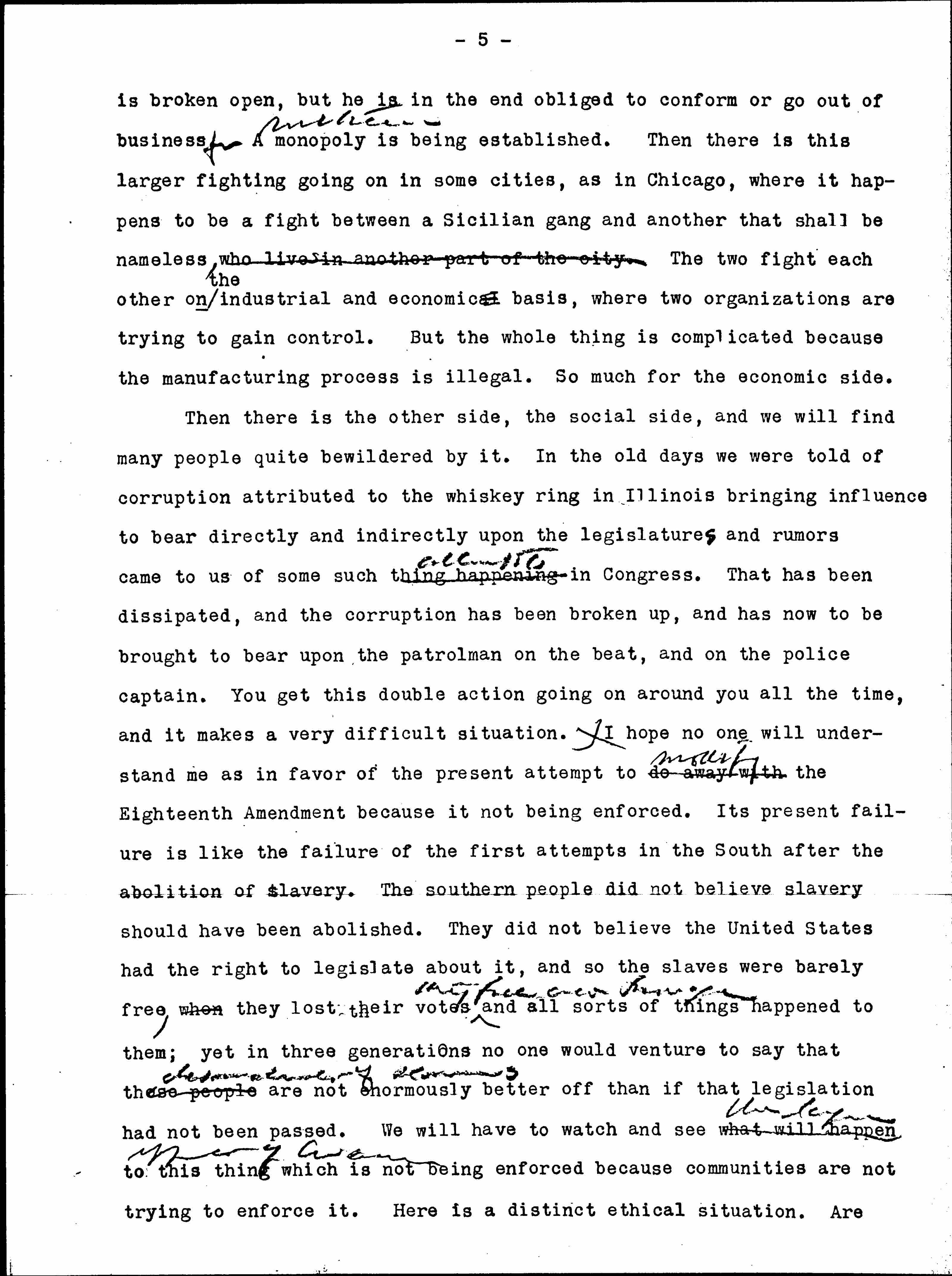

Let us take, for instance, this whole question of bootlegging. Some of us come from communities in which bootlegging is practiced, -- sometimes flagrantly and openly carried on ↑always [clandestinely]↓. We discover two things, -- that there are the economic aspects and the ethical aspects. In its economic aspect we see a great industry, formerly carried on in factories and ↑as we may feel that the↓ distilleries and breweries, becoming decentralized and going back ↑in↓ to the home industry stage. This is just the reverse of what has happened in other industries. It has gone past the ↑is [every?] part of this↓ first stage, however [it?] is now coming out ↑[everyone?]↓ of the home, somewhat, at least. We find the exploiter trying to get control of all the stills within a given area. It is like what happened ↑the situation↓ in the Pennsylvania oil fields years ago, when almost any man who had a piece of land where a well could be dug could produce oil. As one man got more than his neighbor, they began to fight each other, and gradually a certain man gained control in his section, and finally some one came to control ↑a large part of↓ the entire industry. We are in the first attempt to gain control. We have men ↑[illegible]↓ who are quite determined to obtain control of this or that ↑a [illegible]↓ area and who say ↑offer↓ to any man who is discovered ↑[illegible]↓ to own a still, we will go ↑a↓ fifty-fifty with you. If he declines, his still is broken up and maybe his head [page 5] is broken open, but he is in the end obliged to conform or go out of business ↑for↓ a ↑ruthless↓ monopoly is being established. Then there is this larger fighting going on in some cities, as in Chicago, where it happens to be a fight between a Sicilian gang and another that shall be nameless who lives in another part of the city. The two fight each other on ↑the↓ industrial and economic basis, where two organizations are trying to gain control. But the whole thing is complicated because the manufacturing process is illegal. So much for the economic side.

Then there is the other side, the social side, and we will find many people quite bewildered by it. In the old days we were told of corruption attributed to the whiskey ring in Illinois bringing influence to bear directly and indirectly upon the legislatures and rumors came to us of some such thing happening ↑attempts↓ in Congress. That has been dissipated, and the corruption has been broken up, and has now to be brought to bear upon the patrolman on the beat, and on the police captain. You get this double action going on around you all the time, and it makes a very difficult situation. I hope no one will understand me as in favor of the present attempt to do away ↑modify↓ the Eighteenth Amendment because it not being enforced. Its present failure is like the failure of the first attempts in the South after the abolition of slavery. The southern people did not believe slavery should have been abolished. They did not believe the United States had the right to legislate about it, and so the slaves were barely free, when they lost their votes ↑they fell into peonage↓ and all sorts of things happened to them; yet in three generations no one would venture to say that these people ↑descendants of slaves↓ are not enormously better off than if that legislation had not been passed. We will have to watch and see what will happen ↑the larger aspect of [amendment?]↓ to this thing which is not being enforced because communities are not trying to enforce it. Here is a distinct ethical situation. Are [page 6] social workers conscientiously trying to analyze it? That is a real challenge. If we can do it we may be thought worth our salt.

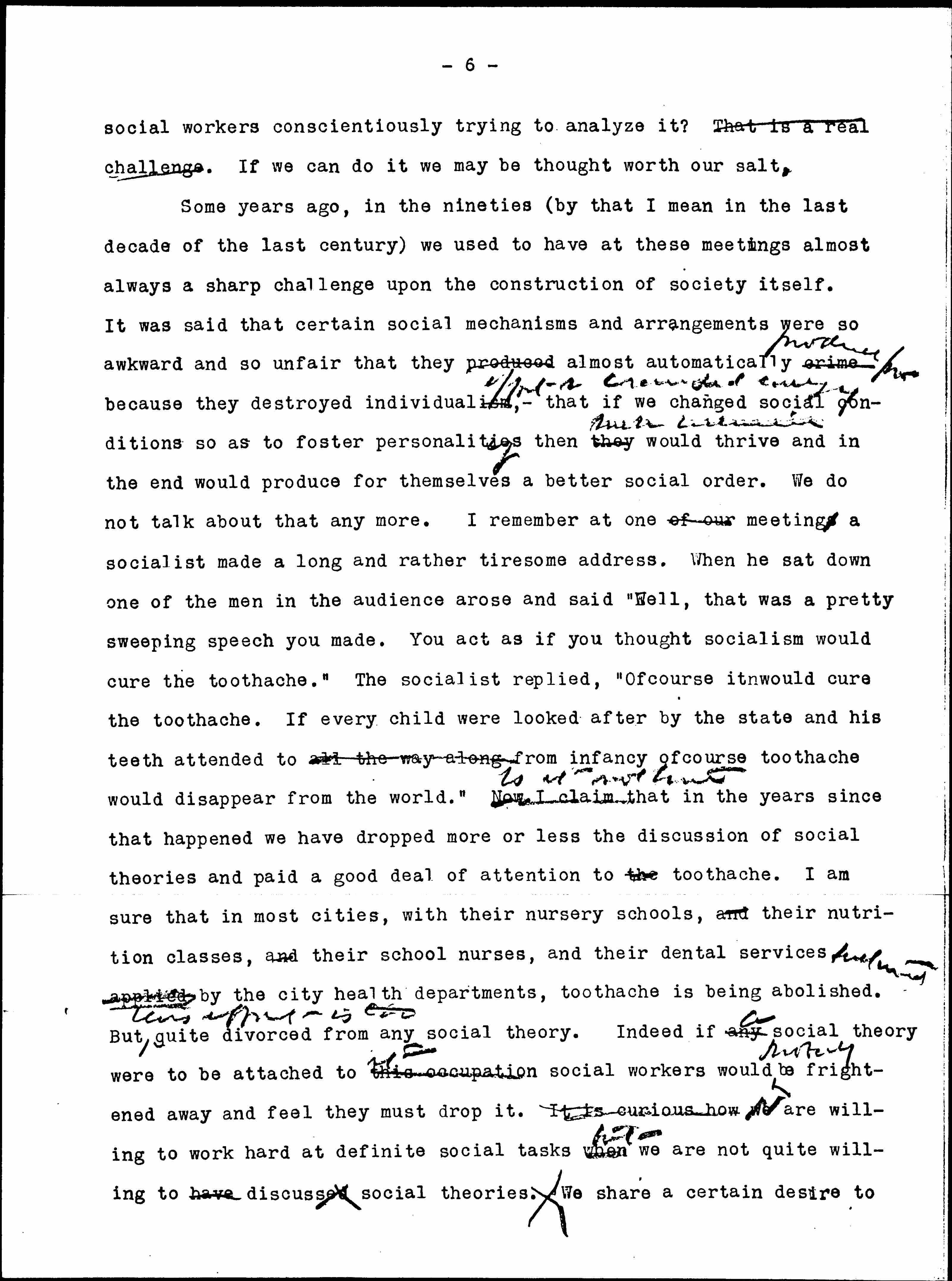

Some years ago, in the nineties (by that I mean the last decade of the last century) we used to have at these meetings almost always a sharp challenge upon the construction of society itself. It was said that certain social mechanisms and arrangements were so awkward and so unfair that they produced almost automatically crime ↑produce [?]↓ because they destroyed [individual] ↑effort & cramped energy↓, -- that if we changed social conditions so as to foster [personality] then they ↑such individuals↓ would thrive and in the end would produce for themselves a better social order. We do not talk about that any more. I remember at one of our meeting a socialist made a long and rather tiresome address. When he sat down one of the men in the audience arose and said "Well, that was a pretty sweeping speech you made. You act as if you thought socialism would cure the toothache." The socialist replied, "Of course it would cure the toothache. If every child were looked after by the state and his teeth attended to all the way along from infancy of course toothache would disappear from the world." Now, I claim ↑It is not true↓ that in the years since that happened we have dropped more or less the discussion of social theories and paid a good deal of attention to the toothache. I am sure that in most cities, with their nursery schools, and their nutrition classes, and their school nurses, and their dental services ↑sustained↓ applied by the city health departments, toothache is being abolished. But ↑this effort is [the]↓ quite divorced from any social theory. Indeed if any ↑a↓ social theory were to be attached to this occupation ↑[it]↓ social workers would ↑probably↓ be frightened away and feel they must drop it. It is curious how We are willing to work hard at definite social tasks when ↑but↓ we are not quite willing to have discuss social theories. We share a certain desire to [page 7] conform and to be safe. That has registered most conspicuously in the field of politics, but it spreads over into other fields. Whether it is a passing phase with us, something to be ↑we can↓ share with the rest of the world, I am not wise enough to say. I merely call your attention to it as an interesting situation. I think we would rather see children freed from toothache than to have the whole effort called "bolshevist." We are in this curious stage of being afraid of generalizations, of being not interested in them, of being anxious to stick to the individual.

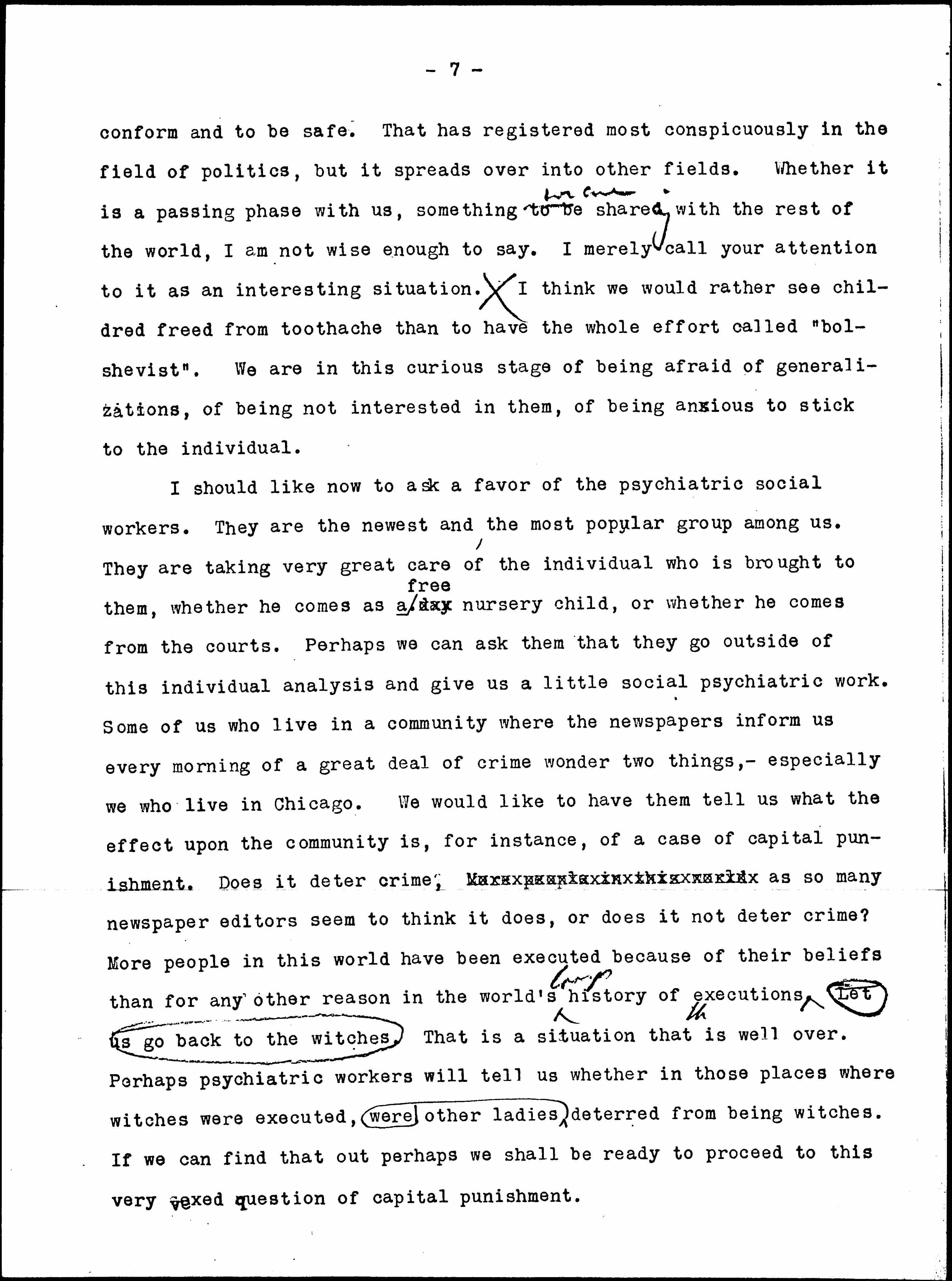

I should like now to ask a favor of the psychiatric social workers. They are the newest and the most popular group among us. They are taking very great care of the individual who is brought to them, whether he comes as a ↑free↓ day nursery child, or whether he comes from the courts. Perhaps we can ask them that they go outside of this individual analysis and give us a little social psychiatric work. Some of us who live in a community where the newspapers inform us every morning of a great deal of crime wonder two things, -- especially we who live in Chicago. We would like to have them tell us what the effect upon the community is, for instance, of a case of capital punishment. Does it deter crime, [illegible] as so many newspaper editors seem to think it does, or does it not deter crime? More people in this world have been executed because of their beliefs than for any other reason in the world's ↑long↓ history of executions. Let us go back to the witches. That is a situation that is well over. Perhaps psychiatric workers will tell us whether in those places where witches were executed, other ladies were deterred from being witches. If we can find that out perhaps we shall be ready to proceed to this very vexed question of capital punishment. [page 8]

They might ↑in time venture to↓ tell us that it was a very bad thing to have a states attorney get great acclaim and many votes according to the number of men he had prosecuted and "sent to the chair," as you ↑they↓ say in New York, or "to the noose" as we refer to it in Illinois. I am sure they would say it was not a good thing for a policeman to gain promotion according to the number of arrests he made. I am sure they would say all of those things had a sadistic (↑you see↓ I am trying to acquire the language of psychiatry) effect upon the community. We now ask them to get back a little from a purely individual study into something which considers the many, and give us some conclusions which may clear our poor bewildered minds. I am saying this not as a social worker, but as an old woman who is perplexed by a situation such as we live in the midst of ↑have↓ in Chicago. At the present time we are astounded by the spectacle of an assistant states attorney being shot in an automobile in company with a man whom he had prosecuted recently ↑tried for murder↓. It is a ↑We are startled by a↓ curious connection, which at the same ↑at↓ times between the forces which we have ↑been↓ elected to take care of the public safety and the elements in the community which are engaged in breaking down public safety. We see it whether in connection with the enforcement of the Volstead Act or whether with those profounder ↑older↓ laws meant to preserve and cherish human life. This entire situation is but a part of the question of the amount which a ↑challenges the↓ community ought to be able to put out ↑to make↓ in an ethical analysis of itself and of its needs. We may perhaps be presumptuous in saying that social work has any special ethical contribution to make ↑such an [undertaking]↓. We can found that ↑base that↓ claim only on the old belief that the man who lives near to the life of the poor, near to the mother and children of the man who is to be hanged, he who knows the devastating effect of disease and vice, has a ↑an opportunity to make a↓ contribution to make to ↑ethics↓ [page 9] the ethical values of the community. and it may be ↑We will certainly↓ we are losing out on the ethical side of social work because ↑then [illegible]↓ if we are [shirk] that obligation, shirking intellectually, shirking for lack of courage, or because we are not alive to our opportunities and obligations. For the moment that is a plain duty before us.

It is curious to find in certain directions that moral leadership seems to have shifted towards the East. In India some years ago I was being entertained by clubs of social workers consisting largely of young men and young women who hoped in the course of time to be a part of the self government of India, and wished to know how to bring humanitarian efforts into governmental affairs. They were going in for those general philanthropic efforts and educational efforts in the hope of understanding about it all. It was interesting to find there one baffling situation that we never have been called upon to tackle, the general subject or segregation. They were taking hold of it with every possible moral energy and zeal. They have a caste system which is buttressed by thousands of years of habit and the sanctions of religion, called the untouchables. Not only Gandhi is breaking into this subject, but these young people of India who hope to be able to govern their own country and realize that they must bring in every man and the bottom man most of all. Just as China is trying to teach every man to read, so India is trying to reach the untouchables, because they know that in no other way can they carry on self government. From time to time we find this whole situation in different parts of the world. Almost always it comes from the people who are closest to the poor, who carry on their activities in touch with that margin of society where it is breaking down and where it needs ↑must be↓ rehabilitated. That is more [than] ethics. It is religion ↑which has been defined as ethics↓ tinged with emotion, In India it is tinged ↑[drenched]↓ with emotion and positive ↑would better describe the [eastern?] movement↓ religious [page 10] urge.

So we come back to the place from which we started, -- how much social work can a community afford from the ethical point of view? Perhaps we need more "sea room," to refer to Dr. Cabot's story of the other night. I heard of a boy who dreamed that he was being pursued by three social workers, all dressed in black and wearing glasses. Just as they were about to catch him he woke up all in a tremble and said to his brother: "Move over, I must have room." Perhaps that is what the social workers need, -- more room. However, we shall use our room to little advantage unless we give back this contribution to the community. A friend gave me an article from a morning paper today in which I was held up as the leader in the period of pre-efficiency in social work. I naturally didn't like it, but perhaps it does define our early efforts. We did not have the schools in which people are now trained and which we admire and try to help somewhat in the spirit of the seniors who vote compulsory chapel for the freshman. We admire the efficiency of the present social worker. In many ways I suppose we do represent the people of thirty years ago, with pre-efficiency standards. We are grateful to any group of investigators who will make social work more efficient, but we do beg for room, and for a chance to pool our impressions of ethical standards with those other people in the community who are living as best they may in this bewildering old world of ours.

Comments